Lack of Access to Maternal Healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa

By Sierra Flake

Published Winter 2022

Special thanks to Hannah Pitt for editing and research contributions

Summary+

Maternal healthcare provides essential care to keep women and newborns healthy during pre-birth visits, delivery, and after birth. In Sub-Saharan Africa, factors inhibiting women from receiving quality maternal care include distance, poverty, quality of maternal healthcare, family dynamics, and cultural beliefs. Lack of access to maternal healthcare has led to severe maternal and neonatal mortality, morbidity, and lack of family planning in Sub-Saharan Africa. Though lack of maternal healthcare is still an issue, significant improvement has been made since 2000 due to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Midwifery and mobile outreach services for family planning are prime examples of practices to improve the maternal healthcare situation in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Key Takeaways+

Key Terms+

Antenatal Care—Maternal care during pregnancy or before childbirth.1

Contraceptives—Medication used to control sexual reproduction by preventing women from getting pregnant. Contraceptives are also known as birth control and refer to a variety of methods: preventing sperm from interacting with the eggs; preventing a woman’s ovaries from releasing eggs to be fertilized; implanting IUDs into a woman’s uterus; and sterilizing a woman, which permanently disables a woman from getting pregnant.2

Family Planning—Family planning allows individuals and couples to anticipate and attain their desired number of children and the spacing and timing of their births. This goal is accomplished with the use of contraceptives along with necessary training and education about safe contraceptive use and sexual lifestyle habits.3

Maternal Mortality—The death of a woman during pregnancy or within 42 days after pregnancy due to pregnancy-related causes.4

Maternal Pathway—The process in which a mother receives maternal healthcare services during all phases of maternity: pregnancy, childbirth, and after childbirth.5

Morbidity—The condition of suffering from a disease or medical condition.6

Neonatal Mortality—The death of a newborn child during the first 28 days of life.7

Obstetric Care—The care and treatment of women in childbirth, before delivery, and after delivery.8

Preterm (premature)—A baby born at 37 weeks into gestation (pregnancy).9

Skilled Birth Attendant/Personnel—Skilled birth attendants or personnel are (1) competent maternal and newborn health professionals; (2) educated, trained, and regulated to national and international standards; and (3) supported within an well-established health system. Attendants play an essential role in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality, therefore keeping mothers and newborns healthy.10

Context

What is maternal healthcare and how is it administered?

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines maternal healthcare as “the health of women during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period. Each stage should be a positive experience, ensuring women and their babies reach their full potential for health and well-being.”11 This definition mentions the health of the woman and her baby because while maternal healthcare is primarily for the mother, a mother’s health directly affects the health of the newborn.

The WHO’s definition also categorizes maternal healthcare into three phases: antenatal care, childbirth, and postnatal care. In each of these phases there are several services provided for mothers. Maternal care during pregnancy or before childbirth is known as antenatal care. WHO recommends at least four antenatal visits to provide adequate time for women to receive the necessary services given by antenatal care.12, 13 These services include vitamins to prevent malnutrition, instruction on healthy habits to follow during pregnancy, emotional and psychological support, relief from pregnancy symptoms, and overall comfort through pregnancy.14, 15 A maternal and fetal assessment is performed during antenatal visits to test for HIV and other health conditions that are likely to have a negative effect on the child, the mother, or childbirth.16, 17 Childbirth, the second phase of maternal care, provides services such as induced labor; monitoring for birth complications; preventive postpartum symptoms treatments; pain relief; and assisted delivery.18, 19 The most conducive environment for these services is an adequately staffed and supplied healthcare facility.20 In case of life threatening emergencies, surgical procedures such as cesarean sections (C-sections), episiotomies (making a small cut in the vagina), and other emergency obstetric procedures are performed during childbirth.21, 22 Finally, postnatal care consists of at least four postnatal visits for all mothers and newborns at specific checkpoints within the 6-week period after childbirth.23 The services provided during postnatal care include assessment of the mother, counseling for birth recovery, psychological support to prevent postpartum depression, and supplements or nutrition counseling.24 Postnatal care helps mothers recover from childbirth and ensure they are healthy enough to care for their newborn baby.

Another essential part of maternal healthcare is family planning and safe sexual behavior counseling. Maternal health guidelines suggest women receive medical counsel about birth spacing, the use of contraceptives, and the use of condoms.25 Safe sexual behavior protects mothers from contracting HIV, and family planning reduces the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.26, 27

How are outcomes from maternal healthcare measured in this region?

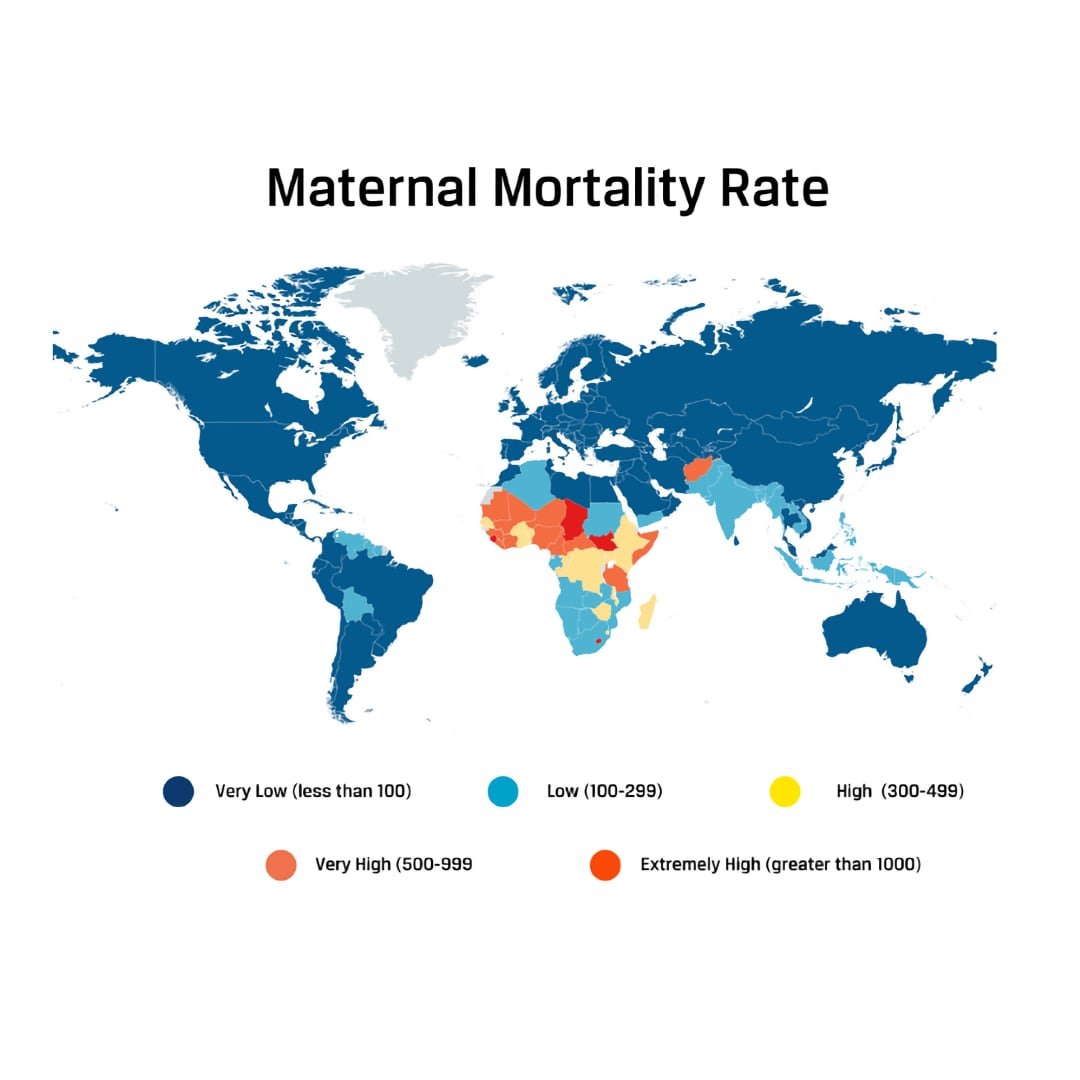

The most common data used to measure the outcome of maternal healthcare at a global scale is maternal mortality, neonatal mortality, and the number of births attended by a skilled birth attendant. These measurements are observed and compared between regions to monitor quality and access to maternal healthcare globally. For example, most countries have less than 100 maternal deaths per 100,000 births, while rates in Sub-Saharan Africa are more than 5 times that rate.28 Accordingly, an infant is 10 times more likely to die if they are born in Sub-Saharan Africa than a higher-income country.29 Similarly, many countries have above 95% delivery coverage by a skilled birth attendant but Sub-Saharan Africa has only 64%. Based on these comparisons, Sub-Saharan Africa has been identified as the location of the world’s highest mortality rates related to maternal healthcare and the lowest percentage of births attended by a skilled professional.30, 31, 32

What does the current maternal healthcare system look like in Sub-Saharan Africa?

The maternal healthcare system in Sub-Saharan Africa is in a poor state compared to other regions. There are not a lot of details known about how the maternal healthcare system works in Sub-Saharan Africa and how the maternal healthcare system in this region compares to maternal healthcare systems in other countries. However, the high percentage of maternal deaths (and lack of birth coverage discussed in the previous section) is an indicator that the maternal healthcare system in Sub-Saharan Africa is not as effective as maternal healthcare systems in other countries. There are approximately 810 global maternal deaths every day, and Sub-Saharan Africa makes up the majority (two-thirds) of those deaths.33 On average, this statistics equates to 540 maternal deaths per day in the region of Sub-Saharan Africa.

The maternal healthcare system in Sub-Saharan Africa follows the maternal pathway explained in the beginning of Context (see “Q: What is maternal healthcare and how is it administered?”). Unfortunately, the percentage of women who continue to access maternal healthcare decreases between each step of the maternal pathway. In the end, less than 20% of the women who receive at least one antenatal care visit will finish the entire maternal pathway.34 In comparison, 85.6% to 93.8% of women received antenatal care in the United States.35 Barriers that keep women from accessing the maternal healthcare system and affect their ability to complete the maternal pathway will be discussed later in this brief.

How has this region fared in reaching international goals concerning maternal healthcare?

It is difficult to assume what practices of maternal healthcare in Africa were used historically due to a lack of public information. However, it is likely that many, if not most, child births throughout the years have occurred without any kind of professional healthcare. Most of the data available on maternal healthcare begins in the year 2000 with the signing of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The MDGs, created to unite country leaders in solving global issues, targeted improving maternal mortality as one of eight focus areas. In 2015, most of the countries in Sub-Saharan Africa were behind in reaching criteria for the MDGs and the African region was highlighted as one of the reasons the goals were not met.36, 37

The MDGs did not completely succeed; however, they did improve maternal healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa. For instance, from 1990 to 2008 the percentage of deliveries attended by a skilled professional increased by 4% in Sub-Saharan Africa. Over the last 20 years, birth coverage has grown by almost 30%.38, 39 Since the region of Sub-Saharan Africa extends over many countries and includes over 1 billion people, a 30% increase affects several thousands of births.

Where is Sub-Saharan Africa and how serious is the maternal health care issue there?

The region of Sub-Saharan Africa is located south of the Sahara Desert. It is made up of 48 countries, including Ghana, Nigeria, and Kenya, and has a collective population of 1.14 billion people.40, 41 The countries of Sub-Saharan Africa are diverse and are not equal in terms of overall development and resources, which creates variation in data with respect to maternal healthcare. However, prominent global organizations often refer to the entire region of Sub-Saharan Africa when analyzing data or emphasizing the magnitude of a social issue in Sub-Saharan Africa.42, 43, 44 This merging is common when global organizations compare maternal mortality, neonatal mortality, and delivery care coverage (see “Q: How are outcomes from maternal healthcare measured in this region?”). In many reports, Sub-Saharan Africa or the African region is highlighted as the region struggling the most to maintain global development standards, which includes universal access to reproductive healthcare.45, 46

Contributing Factors

Distance

Long distances between patients and maternal healthcare facilities is the most common cause identified for the lack of access to maternal healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa.49, 50, 51, 52, 53 The difficulty of traveling these distances is exacerbated by poor roads and the rough landscape, which inhibit maternal care utilization because women are unwilling or unable to travel to healthcare facilities.54, 55 Unfortunately, the average distance women live from maternal healthcare facilities is unclear, given that the data regarding geographical accessibility to healthcare facilities does not consider whether or not maternal care is provided. However, we do know that more than 170 million people living in Sub-Saharan Africa live more than 2 hours from a hospital and 40% live more than 4 hours from a hospital.56 A study using data from 14 different countries within the Sub-Saharan region claimed “every kilometer increase in distance to a source of maternity care was associated with a reduction in the odds of using skilled care at birth.”57 On average, 54% of births had skilled care during delivery when facilities were 4 km away, compared to only 46% of births when the facility was 15 km away.58 Although the difference is only 8%, it still equates to thousands of births attended by a skilled healthcare provider. Distance has also been noted to prevent antenatal and postnatal care. In Zambia, each 10km increase in distance from a facility decreased the chances of receiving good antenatal care by 25%.59 In Nigeria, women reported distance as the second main reason for not receiving postnatal care.60 These cases show that distance prevents women from receiving the service they need in each phase of the maternal pathway.

Another aspect to consider is that even if the facility provides obstetric care, the facility may not offer all maternal healthcare services. According to the joint standards established by United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), WHO, and United Nations Children's Fund, for every 4 facilities that offer basic emergency obstetric care, only 1 facility is required to offer comprehensive emergency obstetric care, because of the additional staff and specialized training required to perform services such as Cesarean section, safe blood transfusions, or administering anesthesia.61 Patients in need of comprehensive emergency maternal care service may need to travel to a specialized facility, which is usually further away and has an even smaller chance of being utilized compared to a general healthcare facility.62

The cost of transportation further complicates travel to a facility.63 Since hospitals are common in wealthy, urban areas and are scarce in poor, rural areas, women traveling the furthest for maternal healthcare are harmed the most by the cost of transportation and the poor road system.64 In poor, rural areas of Sub-Saharan Africa, the most common types of transportation other than walking are bicycles, tricycles, and motorbikes—all risky for expecting mothers.65 Other transportation options are limited, with a lack of public transportation in rural areas and unreliable or unavailable emergency transportation, such as ambulances.66, 67, 68 Common reported concerns with emergency transportation include ambulances vehicles being “out of function,” personnel not responding to phone calls, or personnel not coming immediately when called.69 Long distances to specialized facilities, poor roads, cost, unsafe transportation, lack of public transport, and unreliable emergency transportation all contribute to difficulties in planning and traveling to a healthcare facility, which prevent women from accessing maternal healthcare.

It is important to recognize that there are a few limitations to measuring distance to maternal healthcare facilities. Many studies regarding distance do not specify whether or not the healthcare facilities offer maternal healthcare. In addition, distance and the time spent to reach the nearest healthcare facility are either self-reported or estimated by geographical data.70 These methods lead to inaccurate results and usually do not specify what form of transportation is being used.71 In addition, most research models assume that to travel to a health facility is in a straight line. A new model created to account for competing health care facilities, transportation, elevation, and natural barriers was used in Kenya and found that only 63% of the population was within 1 hour from a government health service building rather than 82% estimated by the usual model.72 Ignoring confounding factors and a lack of specificity when measuring distance or travel time to nearest healthcare facilities makes it difficult to completely analyze how distance contributes to lack of access to maternal healthcare, however it is evident that distance does decrease the likelihood of receiving maternal care.

Poverty

The socioeconomic consequences of poverty often determine an individual’s ability to pay for care. Because most maternal healthcare facilities are built in urban areas, impoverished communities (not just individuals) are less likely to have access to such care.73, 74, 75 The women most at risk of not having access to maternal care are women who live in resource-poor countries, who have a low monthly income, and who have little government support.76, 77 According to the United Nations (UN), the chances of a woman dying in childbirth in Sub-Saharan Africa is 1 out of 16, compared to 1 out of 2,800 for women in the “developed world.”78 It is uncertain what defines a country as “resource-poor,” but these are conditions that are used to describe countries with a higher risk of not having access to maternal healthcare. In addition to the fact that Sub-Saharan Africa has been identified for lack of maternal healthcare, it is likely that the countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are identified as “resource-poor” because of the economic situation of individuals and households. In 2018, 40% of the population in Sub-Saharan Africa were living on $1.90 a day, and in 2020 the number of citizens in poverty increased.79

The increasing problem of poverty means there are an increasing number of women living on little income. In 2017, the maternal mortality rate was 462 per 100,000 pregnancies in low-income countries and 11 per 100,000 pregnancies in high-income countries, which shows that Sub-Saharan Africa is likely to have more maternal deaths due to the amount of people living on little income.80 The association between maternal death and lack of access to maternal healthcare is influenced by poverty because women typically pay out of pocket. For instance, the price of one maternal healthcare visit in Sub-Saharan Africa equates to about one month of untouched earnings.81 Therefore, women living on a low-income struggle to afford maternal healthcare, which makes low income a barrier.

Quality of Healthcare and Healthcare Providers

Poor quality maternal healthcare and healthcare providers negatively influence a community’s trust in maternal healthcare, leading to fewer visits. In a study testing the reputation and effectiveness of free maternal healthcare, 61.5% of women in Sub-Saranhan Africa were unsatisfied with their care.82 Dissatisfaction with healthcare providers and the maternal healthcare system is influenced by a lack of knowledge regarding the practices and benefits of maternal care. When women lack confidence in healthcare providers and systems, they are less likely to seek out maternal care.83

Women are likely to experience concern and uncertainty in giving birth at a facility or with a trained professional if childbirth is a new experience, especially since regional tradition suggests women are more accustomed to giving birth at home.84, 85 In Ghana, many facilities have the reputation of being understaffed, lacking supplies, and having limited availability, all of which concern women that they might be neglected during labor without the certainty of securing support for basic needs such as food, water, and other necessities during labor.86, 87

Abuse perpetrated by healthcare providers also leads to a loss of trust in maternal healthcare and providers. For instance, women in Ghana expressed fear of physical and verbal abuse from midwives in healthcare facilities.88 Another study that collected reports from women in Ghana, South Africa, Nigeria, and other Sub-Saharan Africa countries, confirmed cases of women being physically, sexually, or verbally abused during childbirth.89 In Tanzania and Nigeria, 98% of women receiving postpartum immunizations reported being mistreated during childbirth. In addition, 36% of these women claimed to have been physically abused.90 Bribery in the healthcare system has also been noted as a significant barrier to receiving healthcare. For example, one study reported that 14% of 31,322 people surveyed from 32 Sub-Saharan countries were forced to pay a bribe for healthcare.91 Negative experiences and bad reputations contribute to a general apprehension of seeking maternal care.

Interpersonal level: Influence of Family Dynamics

Family dynamics, especially between the wife and the husband, have a significant influence on access to maternal care, particularly access to family planning. When husbands are educated and supportive of maternal healthcare, women are more likely to receive maternal services.92 In Sub-Saharan Africa, 81.6% of women who received the first antenatal care visits were accompanied by their husband, therefore the majority of women who received antenatal care showed signs of having husband support.93 Education regarding maternal healthcare is also important, 30% of men from this study covering Sub-Saharan Africa had no knowledge about contraceptive use.94 In Africa, husband approval of contraceptive use is claimed to triple the chances of a woman using contraceptives.95 Though the definition of “husband’s approval” is unclear, couple communication plays a role.96 In Nigeria less than 25% of men discussed family planning with their spouses and in Ethiopia it was less than half the men that were interviewed.97 Women are also less likely to receive maternal healthcare if they are single mothers.98 For ages 18 to 60 years, Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest percentage of single mothers at 32%.99 On the Ivory Coast in Africa, women in polygamous marriages and women who were separated were less likely to report having their most recent child in a health facility than women in monogamous marriages.100 In Kenya, the same was true of women who were never married and women who were separated.101 It is uncertain why marital status and access to maternal healthcare is connected; however,a suggested reason has been that without a husband women do not have the financial means or husband support to utilize maternal healthcare.102

Maternity Cultural Beliefs and Traditional Practices

Cultural beliefs and traditional practices in Sub-Saharan Africa can lead to practices that are used as a replacement for modern maternal services, creating a barrier to maternal healthcare. In Ghana, historical cultural and religious beliefs discouraged or inhibited women from seeking professional assistance with childbirth.103 For example, giving birth at home is encouraged because the practice represents strength and integrity; this perspective is common amongst the whole Sub-Saharan region.104, 105 Traditionally in Sub-Saharan Africa, pregnancy and childbirth are an opportunity for a woman to prove herself and claim her position in society. It also brings the woman respect when she gives birth without any assistance. This cultural view can lead to practices that increase the chance of a woman giving birth without the aid of maternal healthcare, and, by extension, increase the odds of birth complications.106 Overall, mothers will often give birth without a skilled birth attendant present (46%) either because a family member encouraged the practice or because the mother opted not to ask for special permission to give birth at a healthcare facility.107, 108, 109

Women often choose traditional practices rather than maternal healthcare because of cultural fears and misunderstandings of obstetric complications.110, 111 In northern Ghana, having a child in a facility is considered “taboo,” and people believe that the ancestors will disapprove and consequently threaten the life of the unborn child, which keeps women away from giving birth in facilities.112 Aside from the taboo surrounding childbirth, cultural beliefs about obstetric complications are mainly based on the idea that any problems that occur during childbirth are a result of the mother’s poor behavior. In many of the communities in Sub-Saharan Africa, obstetric complications are explained by the influence of evil spirits or punishment for disobedience or adultery.113 Due to the nature of the traditional explanations, there is a common belief that maternal healthcare will have no positive effect reducing obstetric complications.114 In these cases, the belief that maternal healthcare is not needed makes traditional practices more favorable and creates a barrier to accessing maternal healthcare.

Consequences

Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

Maternal mortality is the leading cause of death and disability for reproductive-age women in low-resource countries, which includes the African region.115 These deaths are a result of complications that arise from inadequate maternal care, which include but are not limited to lack of education regarding healthcare during pregnancy; a skilled attendant at birth; facility births; and maternal services after childbirth.116, 117 Maternal mortality and morbidity are mainly affected by infections during pregnancy and life-changing or life-threatening conditions from child delivery. The most common complications include severe bleeding, infections, high blood pressure during pregnancy, complications from delivery, and unsafe abortion; these complications account for 75% of maternal deaths.118 The majority of complications that lead to maternal mortality arise during pregnancy or were pre-existing conditions worsened by pregnancy.119

During pregnancy, women are more susceptible to disease and are often underweight because of malnourishment and/or walking long distances for water. Mothers can become infected through unsanitary water, unhygienic living environments, and malnutrition. Common diseases during pregnancy are hookworm, diarrhea, hypertension and pre-eclampsia.120 Most of the complications that arise during pregnancy are avoidable or treatable through maternal healthcare; without access to that care, the result can be more complications or death.121

Life-changing or threatening conditions from delivery include HIV and fistulas. In Sub-Saharan Africa, women with HIV are 10 times more likely to die during childbirth than mothers without HIV.122 This statistic is relevant to the magnitude of maternal mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa because, in 2011, 92% of pregnant mothers diagnosed with HIV in the world were living in Sub-Saharan Africa.123 Fistula is a hole in the birth canal that leads to body fluid leakage. It is caused by intense pressure on the tissues in the pelvic area. If skilled obstetric care intervenes, fistulas can be avoided; if not, fistulas become an uncomfortable medical condition that greatly impacts women and their families.124 WHO estimated that 800,000 women were living with fistula in 2012 and the number grows by 20,000 each year.125 Maternal healthcare can be the first defense against preventing or curing HIV and fistulas by teaching preventive lifestyle habits, detecting the problem early in development, and administering treatment.126, 127, 128

Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality

Sub-Saharan Africa had the highest neonatal mortality rate in the world in 2019 at 27 deaths per 1,000 live births.129 Some of the causes of this high mortality rate include prevalence of HIV/AIDS and other pre-birth conditions of the mother, preterm birth complications, and post-birth infections/illnesses. HIV/AIDs and pre-birth conditions of the mother can be a risk to the wellbeing of the infant. The UN estimates that in Africa 650,000 children are currently living with HIV/AIDS and approximately 1,000 infected infants are born every day.130 This issue is particularly relevant to maternal healthcare because the main mode of HIV transmission is heterosexual sex, which then passes HIV on to children through the infected mothers. There is no cure or vaccine for HIV, but treatment such as antenatal health assessments that identify HIV infected mothers is available to decrease the negative consequences of HIV through maternal care.131, 132

Preterm birth complications are common causes of neonatal morbidity and mortality that arise during delivery.133, 134 For instance, 60% of the world’s preterm births are in Sub-Saharan Africa, and half of all newborn deaths worldwide are due to preterm births.135 Preterm infants are even more vulnerable to complications and infection than other newborns. Conditions that increase the likelihood of preterm birth are when mothers experience malnutrition, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and infections during pregnancy. Antenatal care provides fetal and maternal assessments for health problems that could increase the chance of preterm births, along with educational resources to help mothers decrease the likelihood of having a preterm birth.136 Tetanus, sepsis, pneumonia, and malaria are other leading causes of neonatal morbidity and mortality that affect neonates after birth.137, 138 The risk of infant mortality is highest within the first month of life, which is why it is imperative for women to receive postnatal care.139 Few infants stay in the hospital 24 hours after delivery and are discharged early.140 When infants are discharged early it makes it more difficult for the newborn to receive the postnatal care to prevent illness and ensure the health of the infant, such as skin-to-skin contact; hygienic umbilical cord and skin care; early and exclusive breastfeeding; assessment for health problems and care if needed; and preventive treatment such as immunizations.141

Lack of Family Planning

Maternal healthcare provides women with both education and access to family planning resources through access to contraceptives, sexual behavior counseling, and protection against sexually transmitted diseases.142 These services can prevent unintended pregnancies and improve birth spacing.143 Among surveys assessing satisfaction with family planning services in Africa, more than 50% of women were pleased.144, 145 As of 2019, only 23.7% of women in Sub-Saharan Africa use forms of contraceptives.146 This means that more than 75% of women are not accessing an essential tool of family planning to control birth spacing and number of births. As a result, the unintended pregnancy rate is 29%, which equates to several million unplanned pregnancies a year.147 The consequences due to lack of family planning are also seen in the prevalence of HIV among women in Sub-Saharan Africa. In 2011, 92% of pregnant mothers in the world diagnosed with HIV were living in Sub-Saharan Africa.148 Since maternal healthcare provides women with sex education, such as using condoms for sex, education decreases the spread of HIV.149 Therefore, the high percentage of women with HIV is some evidence that there is a lack of access to family planning maternal healthcare.

Practices

Millennium Development Goals

Eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) exist to combat poverty, hunger, disease, illiteracy, environmental degradation, and discrimination against women.150 These goals were signed in September 2000 by the leaders of 189 countries, who agreed to meet said goals by 2015.151 Each MDG includes targets with quantifiable values in order to measure progress by comparing new data to data recorded in the 1990s, which the goals were based on.152 Organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and WHO have all contributed to collecting data and implementing programs to achieve the goals by 2015.153, 154

The fifth Millennium Development Goal is to improve maternal healthcare by reducing maternal mortality rate by three quarters and achieving universal access to reproductive health by 2015.155 In 2015, only 51% of the African region had maternal healthcare coverage; at the time of the report, the maternal mortality rate showed a 43% decrease since 1990.156, 157 These results show progress but also show that they did not meet the MDGs. In June 2012, the UN started working on a set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in preparation for the MDG deadline. After 2015, the fifth MDGs morphed into the SDGs to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.”158, 159 Currently, 17 SDGs focus on sustaining environmental, social, and economic development until 2030.160

There is not a lot of information regarding the actions made by national policy makers of the Sub-Saharan region in response to the MDGs. However, we know of programs and policies put into practice to achieve the MDGs from larger organizations. For example, WHO’s response included setting prevention and treatment guidelines, providing technical support, and assisting national authorities as they develop health policies and plans.161 One of the UN’s contributions is the Millenium Development Goal and Sustainable Development Goal Fund. The fund was created by the UN to support activities created to advance the millennium and sustainable development goals by bringing together UN agencies, national government, academia, civil society, and business.162, 163, 164 Assessing the impact of MDGs is a little different than other practices because these goals are more of a plan than a practice. Practices were created in order to meet the MDGs; however, it is important to discuss MDGs as a best practice because there is not much recorded about improving maternal mortality in Sub-Saharan African until after the MDGs were created. The MDGs are not vetted (evaluated based on the criteria of effective practices of organizations), but they were written and are used by prominent global organizations such as WHO, World Bank, and UNICEF, which makes them a valid practice.165, 166

Since the Millennium Development Goals were signed in 2000, maternal healthcare has improved overall in Sub-Saharan Africa. The percentage of urban women who received antenatal care at least once increased from 84% in 1990 to 89% in 2008.167 The proportion of deliveries attended by skilled healthcare personnel increased from 42% in 1990 to 46% in 2008.168 The number of maternal deaths decreased from an estimated 523,000 in 1990 to 289,000 in 2013.169 These improvements are contributed to the MDGs since the data was collected when the MDGs were in place. The most significant gap to the Millennium Development Goals is that the African region was not on track to reach the MDGs and is still not progressing at the necessary rate to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.170, 171, 172 In 2003, at the pace Sub-Saharan Africa was progressing it would have taken until the 2100s to meet the development goals.173 In some options, Sub-Saharan Africa was highlighted as the “failure” of the MDG campaign compared to other regions.174 The United Nations general recently called for more global, local, and people action to encourage all nations, especially the African region, to renew efforts to achieve the SDGs by 2030. Global, local, and people action include greater leadership; more resources and smarter solutions for SDGs; embedding the need to transition more to policies, budgets, institutions and regulatory frameworks of governments, cities and local authorities; and including civil society, media, private sector, unions, academia, and other stakeholder to strength their efforts in pushing for the required transformations.175

The other gap pertains to information. Although there is research from larger organizations in regards to the effects of the MDG, there is not readily available information regarding the individual nations’ responses to the MDG, especially within the African region. Perhaps the reason it is difficult to find information about how Africa responded to the MDGs is because the individual countries did not have the means to organize the programs or other changes necessary to achieve the MDGs. A member of the Committee for Development Policy, Kerfalla Yansane, discussed the multitude of obstacles to achieving the MDGs for Sub-Saharan Africa. He then observed that though it is the responsibility of the national policy makers to take change in achieving the MGDs, international countries must also step in to assist Sub-Saharan Africa in order to be successful in achieving the MDGs. Unfortunately, Sub-Saharan Africa has a difficult time trusting donor countries.176 The lack of information makes it unclear exactly what is keeping the African region from being on pace to achieve the MDGs or SDGs. However, it is clear from Yansane’s observations that barriers, such as poverty; declining donor assistance; lack of long-term strategic-planning; and implementing programs that did not align with the MDGs, have been identified and need to be addressed.177

Midwifery

Midwifery is the practice of training and supplying native women to be primary caretakers of mothers during pregnancy, delivery, and after birth in areas where healthcare facilities are not easily accessible. These women promote healthy habits for mothers, know life-saving skills for preventing and recognizing maternity-related health problems, and are trained for emergency obstetric care. Their training also includes sexual and reproductive education. Midwives also provide counseling for gender-based violence, and provide reproductive services for adolescents.178

In addition to global health organizations, several social ventures use midwifery to improve access to maternal healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa, such as mothers2mothers and Every Mother Counts.179, 180 Midwives are typically taught in schools. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), partnered with multiple other organizations, works all around the world to help build schools and train midwives.181, 182 In Africa, UNFPA has contributed to midwifery education programs in Ghana, Somalia, Zambia, Nigeria, Uganda.183 There is not a universal midwife training system, but to ensure that midwives are being trained to provide quality, essential maternal care the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) has established a global standard. A few of the requirements included in the ICM standard for education are that all entry level midwifery students must complete their secondary education, direct entry midwifery program must be at least three years long, post-nursing or health care provider midwifery program must be at least eighteen months, and every midwifery curriculum should be a minimum of 40% theory and 50% practice; the remaining 10% is to give program directors some flexibility in making the curriculum. The ICM standards also include expectations for midwifery teachers and assessment strategies to test the effectiveness of the midwifery students.184

A vital part of training midwives is to equip them with the tools and resources they need for the maternal care they are trained to provide. UNFPA provides midwives with a Minimum Initial Services Package, which includes the resources and activities to save lives of mothers and children during common maternal related complications.185 UNFPA has also created manuals and training guides as resources for midwifery students and teachers.186 Direct Relief is another organization that assists in equipping midwives. They have created a midwife kit endorsed by the International Confederacy of Midwives to supply midwives with the tools needed to support ICM global standards. Direct Relief also provides fistula repair surgeries and multi-vitamins to aid pregnant mothers. These resources are distributed to trained professionals, including midwives, working with maternal care.187

A new, innovative way of training midwives was created by UNFPA with Intel Corporation, WHO, and Jhpiego in 2012. It is referred to as e-learning and m-learning, which is an online system that allows midwives to learn maternal care through online models. This online system can be translated into any language and can be accessed on inexpensive electronic devices without access to the internet. The models included training on emergency obstetric care, family planning, danger signs in pregnancy, and essential newborn care.188 In Ghana over 1,700 midwifery students have been trained through e-learning and m-learning models and in 2019 these models were one of UNFPA’s top resources for training midwives.189

In terms of impact assessments, consequence-based outcome assessments and vetting nothing specific was found for the impact of UNFPA, Direct Relief, or e-learning and m-learning. The International Confederation of Midwives’ global standards established in 2002, which were called The ICM Essential Competencies for Midwifery Practice were evaluated in 2005. This evaluation compared the “essential competencies” to other studies to verify that ICM was using evidence-based research to set their global standards. The result of the study confirmed that the ICM Essential Competencies for Midwifery Practice were based on a variety of quantitative and qualitative methodologies and clinical consensus. Further observation verified that ICM’s standard includes the most essential skills for midwives to learn in order to provide the most quality maternal care and save the lives of their patients.190 Impact research for the other organizations revealed that the e-learning modules from UNFPA have been reviewed and endorsed by professional organizations such as WHO, FIGO, ICM and ICN.191 However, little information was given about how the e-learning modules were reviewed and what qualified it to be endorsed by these organizations. According to the State of World’s Midwifery Report 2011, if midwives are well trained, have the right resources, and women deliver with a midwife present in a facility created for obstetric care it would reduce 61% of maternal deaths and 60% of newborn deaths.192 This statistic shows that the best case scenario to reduce maternal and newborn deaths are a combination of midwifery and facility birth, but since some women do not have access to a facility midwives still contribute to the decrease of death during birth. UNFPA, Direct Relief, and any other organization supporting the practice of midwifery is making an outcome assumption that newborn and maternal mentality will decrease as the number of equipped, quality trained midwives increase because of the improvement seen in maternal healthcare when midwives are involved.193

WHO estimates that 350,000 midwives are urgently needed worldwide, but time and ensuring quality training stands in the way of meeting this need. For instance, the years of school required to train efficient midwives and the development required to create quality training takes a lot of time and effort. Even though the practice of midwifery is improving, a lack of comprehensive midwifery policies, lack of high-quality midwifery education programs, shortage of midwifery trainers, and under-resourced trained facilities still exist. These problems are extenuated by weak midwifery associations that lack poor leadership and are unable to advocate for their needs. Another problem is that often midwifery is not recognized as a profession and these women do not receive adequate recognition for the education they have received or the work they do.194 All of these problems relate to the most prevalent gap in this midwifery, which is that there are not enough midwives. This is evident not only through WHO’s estimate but also by the fact that 50% of trained midwives are no longer practicing midwifery after one year.195, 196 Globally only 30% of midwives completed the full three-year course and only 25% of the 30% that complete the course are trained to meet International Confederation of Midwives standards. Improving the quality of training is important, but it seems that the greater challenge is to ensure that midwifery students will complete the course and remain a midwife after they have been trained.197

Mobile Outreach Service for Family Planning

Mobile Outreach Service for Family Planning is a practice that allows family planning to be delivered through mobile or temporary clinics. Mobile outreach makes it much easier to provide family planning to rural areas or areas that are hard to get to. In Sub-Saharan Africa, 41% of mobile outreach service clients are new to family planning, which means that mobile outreach is making family planning accessible to a much higher percentage of the population. Mobile outreach is accessible and affordable to individuals that live on a low-income, which is evident by the fact that 42% of clients live on less than $1.25 American dollars per day. It also expands the types of contraceptives that can be provided. For example, LARCs and PMs are contraceptives that are more difficult to come by but have a longer-lasting effect.

There are multiple variations of how this mobile outreach is provided. These models are based on where the service is being delivered, the organization providing the service, and the relationship between the provider and those receiving the service. The most common models are referenced as “classic,” “streamlined,” and “dedicated providers.” The “classic” model requires the greatest number of resources. A healthcare provider and a team travels to communities in a mobile clinic or sets up a temporary clinic when they get to their destination. They spend whatever time is necessary to administer contraceptives to their clients and then leave. In the “streamlined” model a few nurses accompany a driver in communities. They use an already existing building like a school, community building, or a client’s home to administer the contraceptives. The third model requires the least number of resources and is called the “dedicated provider” model. In this model, a single provider goes to an already existing healthcare facility and focuses on providing one specific contraceptive, while the other models can give multiple different types.

Mobile outreach is usually implemented or connected with a public health authority or already existing healthcare system.198 USAID is an organization that practices and funds mobile outreach services.199, 200 Mobile outreach service has proven to have a significant impact for increasing awareness and use of family planning. Mobile outreach service has been vetted by Family Planning High Impact Practice (HIP) since various models of this practice have been successfully implemented at large scales and have resulted in wanted outcomes.201 One example from the Sub-Saharan African region is Malawi. In Malawi there was a 14% increase (28% to 42%) in modern contraceptive use amongst married women.202 A case study by the health department of Malawi concluded that mobile outreach played a key role in the percent increase.203 A cross-sectional survey conducted discovered that in Uganda and Tanzanian mobile service is preferred instead of static service because the methods have a longer effect.204

USAID through the use of mobile outreach and other family planning promoting innovations reduces maternal deaths by 30% annually and has helped prevent 20,000 maternal deaths and 12.2 million unintended pregnancies.205 USAID has funded several studies aimed to assess the impact, effectiveness, and sustainability of mobile outreach. The Respond Project and the Adventist Health Service both evaluated that the mobile outreach service was successful in improving access to family planning.206, 207 Gaps in mobile outreach service for family planning include potential problems in transportation, misunderstandings between clients and providers about family planning, and lack of follow-up care.208 There is also a lot of controversy regarding where medical waste will be disposed of and the fact that the services are irregular, instead of consistent.209 Another problem is ensuring follow-up care because the mobile service is temporary, and providers and teams change. Solutions to this problem are using mobile phones, hotlines, and SMS follow-up messages and care. However, this may not be an option depending on what is accessible to the community.210 For the mobile outreach service to provide these forms of communication, more funding would be necessary.

Preferred Citation: Sierra Flake. “Lack of Access to Maternal Healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Ballard Brief. March 2022. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints