Lack of Menstrual Hygiene Management Among Women and Girls in East Africa

Photo from www.afripads.com, used with permission

By Lizzie Kearon

Published Winter 2021

Special thanks to Madison Coleman for editing and research contributions

+ Summary

Women and girls in East Africa, as well as many other parts of the world, live in a culture where menstruation and reproductive health are not discussed. This is because menstruation and anything related to it is considered taboo. Both women and girls often do not understand the reproductive cycle of their bodies or know how to manage their menstruation. Girls commonly miss or drop out of school because they do not understand what is happening to them or are unaware of how to hygienically manage their natural cycle. The issue is perpetuated by menstrual hygiene products being expensive and hard to obtain, as well as a lack of easy access to clean water and latrine privacy. Girls are negatively affected in many ways, including a compromised education from missing school, infection or disease due to lack of hygiene, and pressure to engage in transactional sex in order to obtain menstrual hygiene products. Current best practices that aim to improve menstrual hygiene management include providing girls with menstrual hygiene education through workshops and magazines, and increasing accessibility of menstrual hygiene products through distribution of reusable pads.

+ Key Takeaways

+ Key Terms

East Africa - This brief is focused on the East African Community, also known as East Africa, which consists of Kenya, Uganda, Burundi, Rwanda, South Sudan, and Tanzania.

Menarche - This is the first occurrence of menstruation.1

Menses - This is the blood and other uterine tissue discharged during menstruation.2

Menstrual hygiene education - Ideally, this is comprehensive education that provides both boys and girls with accurate, timely information on the psychosocial and biological aspects of puberty, menstruation, and menstrual hygiene management.3

Menstrual hygiene management (MHM) - This refers to hygiene associated with the menstrual process, including proper use of menstrual hygiene products and proper washing habits.4

Menstrual hygiene products - Also referred to as “sanitary products,” these are store-bought products (as opposed to homemade alternatives) used to absorb or collect menses. They include disposable products, such as pads and tampons, and reusable products, such as menstrual cups and reusable pads.

Transactional sex - This is the practice of women exchanging sex for money or menstrual hygiene products.5

Context

Almost all women across the world at reproductive age naturally experience menstruation roughly once a month. Girls who are taught to understand how their bodies work and who have access to hygienic methods of managing menstruation are empowered to go about their education, work, and other regular life activities despite their menstrual cycle. In many areas of the world, however, there is a lack of menstrual hygiene management (MHM) which greatly inhibits women and girls’ ability to function as healthy, equal, dignified members of society.6

East Africa is one of the regions in which many women and girls do not have adequate MHM. Also known as the East African Community, this region consists of Kenya, Uganda, Burundi, Rwanda, South Sudan, and Tanzania. Poverty pervades each of these East African countries, with approximately 72% of the population living on less than $3.10 USD a day (Burundi 89%, Kenya 59%, Rwanda 81%, South Sudan 64%, Uganda 65%, Tanzania N/A).7 While these countries are distinct, they share aspects of culture, are partnered states with an established Customs Union and Common Market, and are working toward a Monetary Union and Political Federation.8 They are also tied together by their similar attitude toward and treatment of menstruation.9 Lack of MHM has been studied and shown as an issue throughout many parts of the world, especially sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia,10 but a great number of studies have focused on these East African countries, especially Kenya and Uganda. While differences between the countries are acknowledged, the statistics and anecdotes shared in this brief depict general trends across the region.

Countries in East Africa.

Women and adolescent girls are using a clean menstrual management material to absorb or collect menstrual blood, that can be changed in privacy as often as necessary for the duration of a menstrual period, using soap and water for washing the body as required, and having access to safe and convenient facilities to dispose of used menstrual management materials. They understand the basic facts linked to the menstrual cycle and how to manage it with dignity and without discomfort or fear.11

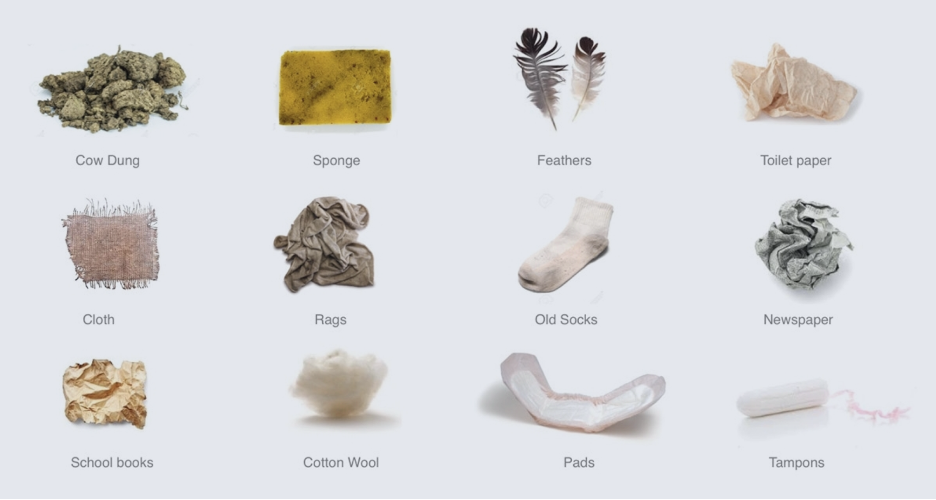

A lack of large-scale data makes it difficult to estimate the proportion of East African women and girls who lack MHM, but small-scale studies generally indicate high proportions. For example, a recent study in Uganda found that 90.5% of study participants failed to meet the criteria for adequate MHM.12 A variety of menstrual hygiene products and homemade alternatives are used across East Africa, and the most common product depends on the area and economic status.13 Studies indicate that most urban women and girls use disposable pads, and most rural women use homemade alternatives. Alternatives include pieces of cloth, toilet paper, news paper, mattress stuffing, etc., or natural material such as leaves, mud, ash, dung, etc.14 15 Disposable and reusable insertables, such as tampons and menstrual cups, exist, but only in certain upper-middle class areas. Insertables are considered a high-barrier product in some areas due to cultural and religious concerns with inserting products and, thus, compromising virginity.16

Menstruation is taboo in East Africa, often even between women, meaning communication barriers are blocking progress toward menstrual hygiene education, and, therefore, healthy MHM.17 In this region, menstrual blood is considered dirty18 and is associated with disease.19 For example, girls in Kenya are told to hide and avoid discussing their menstrual bleeding.20 This taboo is perpetuated because menarche is a cultural signal that a girl is sexually mature and eligible for marriage. Fear of rape or young marriage are some of the reasons why girls keep their menarche a secret from their parents and peers.21 A lack of data means it is impossible to know how long the taboo surrounding menstruation has been part of East African culture. It also means it is difficult to know how long there has been a lack of not only menstrual hygiene education, but also general reproductive health education in schools.

In recent years, MHM has received increased attention around the world from non-profits, development organizations, and governments.22 In East Africa, the rising generations are beginning to talk more about MHM as they are taught about it in school and by various organizations aiming to solve the issue. According to one study in Kenya, however, only 12% of girls would be comfortable receiving the information from their mother.23 This demonstrates that there is still a long way to go before the cultural taboo is dispelled and women and girls are both educated and practicing healthy MHM.

Contributing Factors

Lack of Menstrual Hygiene Education

Women and girls are unable to hygienically manage menstruation when they lack menstrual hygiene education. The cultural taboo surrounding menstruation is arguably the main reason East Africa lacks menstrual hygiene education because when an entire region feels uncomfortable or unable to talk about an issue, educating others on that issue is nearly impossible. In recent years, more youth are learning about puberty and menstruation in school, but students often consider the instruction to be incomplete and inadequate.24 Girls are rarely taught about menstruation prior to their menarche, and most girls tend to first learn about it at school. A recent study in Kenya found that 62.5% of participants first heard about menstruation through school, and 43.8% considered teachers their predominant educators on the subject. Only 6.3% considered their mothers their predominant educators on the subject.25

Since girls are rarely taught about menstruation or how to manage it prior to menarche, they are unprepared, confused, and often afraid when they have their first period.26 A study in Tanzania, for example, found that many girls thought they had a disease or were dying when they experienced menarche, resulting in fear, shame, and confusion. The same study found that perceived early onset of menarche “is sometimes hidden by girls for fear of being accused of premarital sexual activity.”27 A recent study in Uganda reported that 23.8% of school girls questioned knew nothing about menstruation prior to their menarche.28 Another Kenyan study reported that 1 in 4 girls did not know they could get pregnant once starting their periods.29 One girl interviewed in Kenya “knew more about Ebola, of which there’s never been a case in Kenya, than she did about menstruation.” Other girls in the same study thought the only way to get pregnant was through having sex during menstruation.30

Misinformation makes it difficult for women and girls to learn about their bodies and the best ways of managing their menstrual cycles. When adults are misinformed and lack menstrual hygiene education, they cannot teach the younger generation, perpetuating the lack of MHM. A Tanzanian study reported that half of rural participants revealed that the researchers were the first people they had told about their menarche. The reason for their silence was that their primary school teachers had taught that telling one’s mother about one’s menarche would cause her to die—a clear example of misinformation. The same study, however, reported that some girls have mothers who provide guidance (though usually not until post-menarche) despite the taboo surrounding sexual health and menstruation.31 In a study of six Ugandan schools, female teachers reported never having had instruction on menstruation, likely a key factor contributing to the students’ lack of knowledge. Male teachers in the same study displayed disinterest and little sense of responsibility for the issue. When asked what the government should do to support the girls’ MHM, one male head teacher responded that they should provide “special rooms with all the equipment that is needed for ladies,” and then could not give any detail of “what is needed” when probed further. Another responded similarly: “All that is wanted. There are very many—pads, cotton wool. Even some I do not know because I am not female.”32 These responses reveal the male teachers’ lack of knowledge about menstrual needs and reluctance to engage with, what they consider to be, a female issue. This demonstrates that the lack of both female and male education surrounding menstrual hygiene contributes to the lack of MHM.

Expense of Menstrual Hygiene Products

Another factor that contributes to lack of MHM is the great expense of menstrual hygiene products. In one investigation, sanitary pads were found to be the second largest monthly cost, after bread,33 to an average Kenyan family; approximately two-thirds of women and girls in Kenya cannot afford them.34 In Uganda, a package of 10 disposable pads costs $1.35 USD on average,35 which is unaffordable for many households as 35% of Uganda’s population live on less than $1.90 a day (see Table 1 for disposable pad price and income information in other East African Countries).36 On average, nearly 49% of the population of East Africa lives on less than $1.90 a day.37 Additionally, it is possible that the cultural taboo surrounding menstruation means girls feel uncomfortable asking their fathers to buy menstrual hygiene products, so they cannot obtain them even if they have the means to do so.

Lack of Access to Clean Water and Latrine Privacy

East Africa also experiences a lack of easy access to clean water and latrine privacy, making it difficult for women and girls to apply and change their sanitary products. According to a study that looked at six African countries, including Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda, fewer than 23% of rural schools met the World Health Organization’s recommended student-to-latrine ratios for boys and girls. In addition, fewer than 20% were observed to have at least four of five recommended menstrual hygiene services (separate-sex latrines, doors, locks, water for use, and waste bins).38 A study of six government-run schools in rural Uganda reported all of the girls’ school toilets to be inadequate for good MHM due to their lack of cleanliness, light, soap, and water. In addition, the ratio of toilets for the number of girls is lacking and access for disabled girls is especially poor.39 A study focused in Kenya reported that in rural areas, only 32% of schools had a private place for girls to change their sanitary products, let alone water and soap to wash with.40 According to a study at four high schools surrounding urban areas of Uganda, only 14.2% of girls reported always having access to water and soap at school.41

Access to water and soap can also be a challenge at home. For example, it has been found in Uganda that many girls are too ashamed to ask their parents for soap, so they hide pieces of leftover soap after washing the family clothes in order to later wash their menstrual cloth in private.42 This means that even if girls have access to sanitary products or reusable menstrual cloths, there is still the issue of them being able to change and wash their sanitary products hygienically.

Consequences

Reduced Educational Opportunities

Lack of menstrual hygiene education and MHM often leads girls to miss school while on their periods or drop out completely.43 Menstrual-related school absenteeism seems to be worse in rural areas than urban and peri-urban areas. For example, research in rural Uganda found that 61% of participants reported missing school each month for menstrual-related reasons.44 This can be compared to a study in peri-urban Uganda which found that 19.7% of participants reported missing school during their most recent period.45 According to another Uganda study, the main reason girls reported menstrual-related school absenteeism was the lack of a private place for them to wash and change at school (63.8%). This was followed by fear of staining their clothes, then discomfort from bloating and tiredness, then pain. When asked if there were additional reasons for menstrual-related absenteeism not listed in the questionnaire, one girl stated that she was afraid of her menstrual cloth falling out if she was beaten at school.46

Many girls in East Africa who manage to attend school during menstruation do so with low confidence and dignity due to a disregard for their privacy, feelings of shame and embarrassment, and fear of being teased and bullied. These feelings have been found to affect academic performance and interfere with participation in school and extracurricular activities.47 An example is Alice Mwangi, who grew up in a small Kenyan village. As reported by Direct Relief, she experienced her first period at school and was called to the front of the classroom and slapped by her teacher because she was so anxious about the bleeding that she could not answer the question. The embarrassment and trauma led her to perform a ritual that legend claimed would turn her into a boy, and also led her to fail her national exam three days later.48

Absenteeism impedes girls’ ability to compete in the classroom, leads to low self-esteem, raises dropout rates, and, in some areas, increases vulnerability to early marriage.49 Although girls’ school enrollment rates are increasing, large gender gaps in primary education, and even larger gaps in secondary education remain.50 Dropping out of school negatively affects girls’ education and prospects of obtaining a good job in the future, which can act as a barrier for these girls to escape the cycle of poverty. Research shows that educating women is seen as crucial in the fight to eradicate global poverty, meaning these girls dropping out of school perpetuates their country’s state of poverty.51

Infection and Disease

When women and girls have poor MHM, especially in regards to the sanitary products they use, it often leads to chafing, rashes, burning sensations, infection, or disease.52 A lack of data from East Africa makes it difficult to know the prevalence and types of infections and diseases due to lack of MHM; however, available research suggests MHM to be associated with reproductive tract infections (RTI). The RTIs thought to be primarily non-sexually transmitted and most relevant to MHM are bacterial vaginosis and vulvovaginal candidiasis. These vaginal imbalances can be introduced to the reproductive tract through unsanitary materials used for absorbing menses or by poor washing of the body during the menstrual period. They are both associated with an increased risk of HIV.53 This is particularly relevant because, globally, 80% of women living with HIV ages 15–24 live in sub-Saharan Africa (which includes East Africa).54 In addition, 21% of HIV-infected adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa live in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda.55

One study in Tanzania found that, although most women placed cloth inside their underwear and changed it periodically throughout the day to absorb the menses, some inserted cloth into their vagina and left it there for multiple days.56 According to a Kenyan study, of the girls who used sanitary pads, 40.3% delayed changing by over 6 hours.57 Medical professionals recommend using the lowest absorbency tampon or pad necessary, and advise changing tampons at least every 4–8 hours in order to prevent infection.58 Leaving absorbency materials in place longer than this is dangerous and can lead to RTIs. While some numbers are available, more data is needed from East Africa in order to better understand and treat infections and diseases caused by insufficient MHM.

When girls lack the means to manage their menstruation, they often resort to transactional sex. Desperation to obtain sanitary products leads girls to engage in transactional sex for money that they can then use to buy products.59 The noncommercial nature of transactional sex differentiates it from prostitution.60 Women receive around $0.60–1.80 USD per transaction.61 62 A sub-Saharan Africa study found that young, unmarried women are most vulnerable to experiencing transactional sex.63 A recent study in Kenya shows that 1 in 10 girls have engaged in transactional sex to obtain pads.64 Another shows that 2 out of 3 pad users in rural Kenya receive pads from sexual partners.65 A Uganda study found that 75% of sexually active girls received money or gifts in exchange for sex.66

Transactional sex not only means girls and women feel pressure to have sex when they would otherwise choose not to, but it also means they are more likely to have unwanted pregnancies and contract sexually transmitted diseases, such as HIV and AIDS, due to an increased number of sexual partners. This likelihood is worsened by the fact that epidemiological studies have shown transactional sex to be associated with inconsistent condom use.67 In sub-Saharan Africa, young women ages 15–24 have more than twice the risk of acquiring HIV as their male counterparts. A growing body of epidemiological evidence suggests that the practice of transactional sex contributes to this disparity.68 69

Practices

Menstrual Hygiene Education

The first key step in tackling MHM is improving menstrual hygiene education (MHE). Ideally, MHE provides both boys and girls with information that is accurate and timely on the biological and psychosocial aspects of puberty, menstruation, and MHM.70 MHE allows girls to make informed decisions about their MHM, and also simply increases discussion of the topic, thus helping to dispel the menstruation taboo. Currently, since MHE is not a consistent part of East African school curriculums, the best practice for bringing this education to young women is through workshops and magazines.

ZanaAfrica Foundation is one example of this best practice. They provide girls in Kenya with MHE through after-school workshops, known as the Nia Yetu curriculum, and an accompanying reproductive health magazine, Nia Teen. The workshops and magazine discuss both menstrual and general reproductive health topics. Nia Teen is purposely designed as a physical resource so girls can own it, read it in private, refer back to it over time, and share it with others.71 ZanaAfrica has also developed their own locally-made Nia line of sanitary pads, which are high quality, affordable, and provide information on the packaging about reproductive health and family planning.72 These pads can be bought online and delivered anywhere in Kenya.73 A pack of 10 costs 75 KSh74 ($0.69 USD), which is less than most other brands sold in Kenya (see Table 1). Nia pads can also be purchased by donors and distributed to school girls as part of a termly school kit that consists of 32 pads and cotton underwear.75

ZanaAfrica offices are based in Nairobi, with development officers and communications based in the US.76 They rely on voluntary contributions to support their operations and programs, with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation being their most significant funder.77 They have a goal to expand across East Africa and beyond.78 Founder Megan White Mukuria chose the name ZanaAfrica for the organization because zana means tools in Kiswahili, and Mukuria believes the foundation equips girls with the tools they need to define and step into their full potential.79

Impact

ZanaAfrica has provided MHE to over 50,000 girls since 2013.80 In 2018 alone, they shared MHE with nearly 4,000 girls across Kenya in 70 after-school workshops and distributed 35,600 sanitary pads. They also reported training teachers and officials from the Kenyan Ministry of Education on their reproductive health education. These teachers work in 40 schools, directly impacting 1,600 girls.81 One girl who received ZanaAfrica’s MHE reported learning “the truth” about periods and learning that through proper management one can still go on with life activities while menstruating.82

ZanaAfrica is currently conducting a randomized control trial (RCT) in 140 Kenyan schools to determine their impact (see Table 2). They want to know if and how their reproductive health education and sanitary pad distribution is improving girls’ educational and sexual and reproductive health outcomes.83 This RCT, called The Nia Project, is one of the first to explore the role of reproductive health education and sanitary pad distribution—individually and in combination—in improving outcomes. The results will provide a better understanding of the impact of ZanaAfrica and other similar organizations who follow this best practice.84

Gaps

ZanaAfrica has encouraging outputs and is on track to measuring their impact, but they have some gaps in their practice. For example, boys are not included in their reproductive health education workshops. The menstruation taboo in East Africa affects and is perpetuated by both women and men, so for the taboo to be dispelled, and for women to experience equal opportunity at school and work, men must be included in the education and conversation. According to ZanaAfrica, they began after-school workshops in February 2019 that included boys in 10 primary schools.85 The boys are included by bringing them into the girls’ workshops or by creating new workshops tailored to boys’ needs.

Increase Accessibility of Menstrual Hygiene Products

With increasing MHE as the first key step in tackling MHM, increasing accessibility of menstrual hygiene products is the second key step. Most organizations combine this second step with the first in their interventions, like ZanaAfrica, but some make product distribution their main focus. There is a debate over which menstrual hygiene product is best for women and girls in East Africa. Some argue that disposable pads are better because they are what most girls want, and many girls lack the infrastructure and resources (private bathrooms, clean water, soap, etc.) to be able to hygienically manage a reusable product.86 Others argue that reusable products, like menstrual cups and cloth pads, are better because they are cost effective, durable, and waste reducing.87 Waste reduction is an important factor because of the waste management challenges that many countries in East Africa face.88 It is possible that the best product depends on the particular region of East Africa, but generally speaking, reusable pads currently seem to be the most common product chosen and distributed by organizations. This is likely because they are a one-time cost that can last many years, as opposed to a recurring cost and distribution task. Menstrual cups can last up to 10 years,89 for example, and reusable pads can last up to 3 years.90 Of these organizations, a handful, such as The Cup based in Kenya, choose to distribute menstrual cups,91 but most choose to distribute reusable pads, determining it to be the best practice.

AFRIpads is one example of this best practice. Based in Uganda, their main intervention is their locally manufactured reusable pad that lasts for a minimum of 12 months. Since their founding in 2010, they have already scaled outside Uganda to reach 37 countries,92 and are now the world’s leading social enterprise that manufactures reusable sanitary pads.93 They offer a standard 4-pack, a standard 6-pack, a schoolgirl kit, and underwear.94 AFRIpad kits provide menstrual protection “for 12+ months at approximately 30% of the total cost of a one year supply of disposable sanitary pads.”95 AFRIpads also provide a menstrual health and hygiene curriculum in 4 languages as well as the reusable pads.96 They are partnered with over 200 organizations97 including UNHCR98 and the French Red Cross.99 All products are bought and distributed by partner organizations, but can also be purchased by individuals online.100

Impact

AFRIpads menstrual kits have reached 3.5 million women and girls around the world. Over 70% of these kits went to refugee women and girls across Africa.101 AFRIpads’ largest market is in East Africa (Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, South Sudan, and Somalia).102 They have also built menstrual health and hygiene knowledge for 32,500 NGO staff, teachers, and community health workers across 9 countries, thereby helping to educate more than 110,900 women and girls.103 It is unclear to what extent AFRIpads measures their impact, but they offer a complete Data Collection Toolkit to their partners, available on a mobile app, which can be used to complete surveys offline in the field. These surveys include a needs assessment (to be taken pre-intervention), as well as an intervention evaluation (to be taken post-intervention) which determines the extent to which AFRIpads kits and menstrual health and hygiene curriculum have helped in meeting women’s menstrual needs.104 They also claim that their menstrual kits were developed through user-centered design, which involved collaborating with actual school-age girls in their creation.105 After millions sold, the kits are now said to be tried and tested.106

Image from www.afripads.com, used with permission

Gaps

The impact of AFRIpads’ menstrual kit distribution and menstrual health and hygiene curriculum currently seems to be undetermined. In order for them to understand their effect on communities, they should consider conducting a randomized control trial, similar to ZanaAfrica’s, where they measure the changes in girls’ menstrual hygiene, school attendance, etc. from before and after their interventions. AFRIpads could also improve their reach by partnering with stores to sell their products locally. Currently, women and girls can only obtain AFRIpads products through donors or online purchase. Some women may not have reliable internet access, making it difficult for them to order products. Therefore, local in-store purchase options, especially in areas with the greatest need, could be the next step for AFRIpads.

Learn more about AFRIpads by watching this video: The AFRIpads MHM Solution

Preferred Citation: Kearon, Lizzie. “Lack of Menstrual Hygiene Management Among Women and Girls in East Africa.” Ballard Brief. January 2021. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints